This weekend the temporary exhibition, Samuel F.B. Morse’s Gallery of the Louvre and the Art of Invention, opened at Crystal Bridges. It focuses around a single monumental painting by the man most of us are familiar with as the creator of Morse Code. But in addition to his skills as an inventor, Morse was also a skilled painter. His life story is a multi-faceted one, full of bumps and false starts and inventions and re-inventions.

Samuel Finley Morse was born in 1791 in Charlestown, Massachusetts. He traveled to London in 1811, where he was accepted into the Royal Academy. Morse and other American artists abroad were distressed at the general lack of appreciation for art, and opportunities to view great works of art, back home, and Morse became determined to “endeavor … to rouse the feeling for works of art” upon his return to the United States.

Despite his ambitions, Morse had difficulty settling into any one line of work once he got home. He worked as an itinerant portrait painter for a time, but then Morse decided to go into the ministry. it must not have suited him; he lasted just two months in divinity school and then went back to painting portraits. Morse and his brother Sidney also tinkered with inventions. They gained a patent for a leather piston for water pumps, and Morse also invented a sculpture-copying device that he used to successfully copy a bust of Apollo in 1823. But he then discovered that a patent for a similar machine had been granted to another in 1820.

In 1821, Morse set out on his first grand painting project: a large painting of the US House of Representatives in session, for which he completed more than 60 portraits from life. He imagined the work traveling the country and garnering for its artist both admiration and income, but neither materialized. The American public was luke-warm to the work, and Morse determined that “its merit is of too refined and unobstrusive a character” for American audiences unschooled in fine art.

Morse finally caught a break in 1825, when he was selected to paint a full-size portrait of LaFayette for the City of New York. He traveled to Washington DC for the sitting, and created the sketch of the French hero’s head that is now in Crystal Bridges’ collection. But his work was interrupted by the news that his wife Lucretia had died unexpectedly. Morse rushed home, but arrived too late to attend her funeral. Frustrated at the ponderous speed of communication, he began to think about ways to make the relay of important messages faster.

After his wife’s death, Morse lived in New York, where he was elected to the American Academy of the Fine Arts, an organization designed to cultivate appreciation of art, rather than to teach. Students were, however, allowed to come into the gallery at set times to draw from casts of classical sculptures. When the head of the Academy, John Trumbull, locked the students out of the gallery, they petitioned Morse to help, and he set up a Drawing Association that met three evenings a week. Among his students were the young Asher B. Durand and Thomas Cole. In 1826, Morse and his students formed the National Academy of the Arts of Design, modeled after the Royal Academy in London. Morse was elected president, and remained in that office for 15 years.

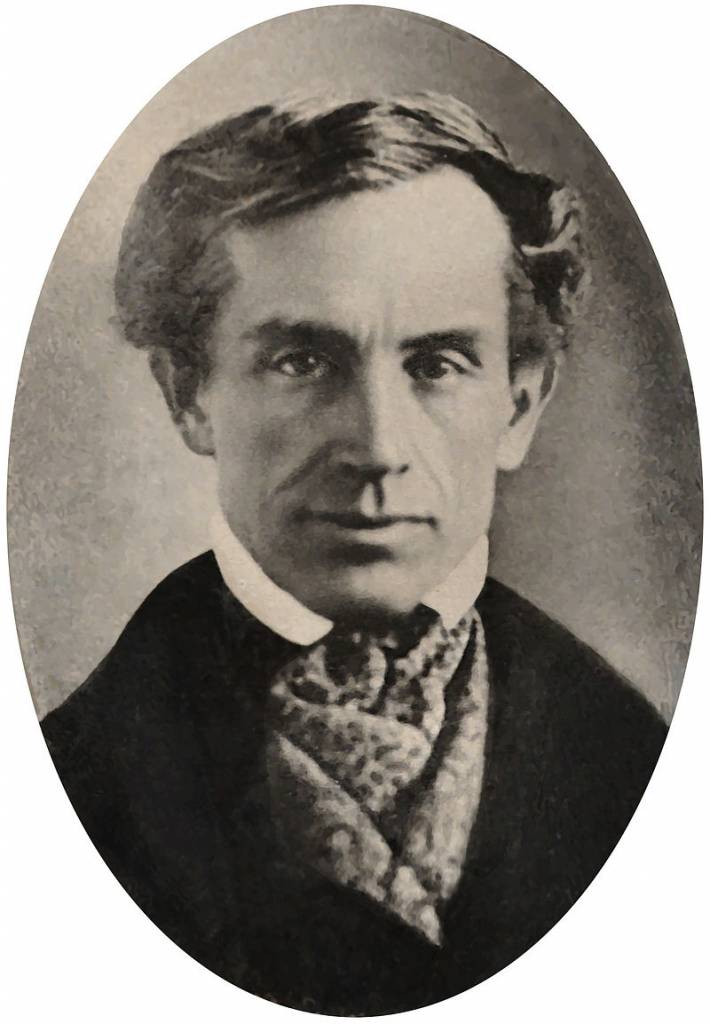

Samuel F.B. Morse, 1791-1872

“Gallery of the Louvre,” 1831-1833

Oil on canvas

Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago, Daniel J. Terra Collection

In 1829, Morse traveled to Paris where he embarked upon his monumental painting, Gallery of the Louvre. Intended as a means of educating the American public about European art, the painting included copies of 38 artworks by Old Masters in the Louvre’s collection. He worked on the painting in his studio, and also in the Louvre itself at times, attracting the attention and admiration of Museum visitors. He hoped for an equally warm reception for the work when he exhibited it in America. Morse returned to the US in 1932, and during the trans-Atlantic crossing he met a man named Charles Thomas Jackson, who talks at length with Morse about electromagnetism, sparking Morse’s idea for the electromagnetic telegraph. In 1833 Morse sent his masterpiece out to tour American cities as a one-painting exhibition. Once again his painting received critical admiration, but fell flat with the public. Morse canceled the tour after only two showings. He was completely demoralized by this failure, and soon afterward gave up painting altogether. Though his plan to educate Americans in the fine arts through his painting failed, in a sense Morse was successful in his early ambition to “rouse the feeling for works of art.” The National Academy that he helped to found has produced generations of artists, including Winslow Homer, George Inness, Arshile Gorky, and Willem de Kooning, among many others.