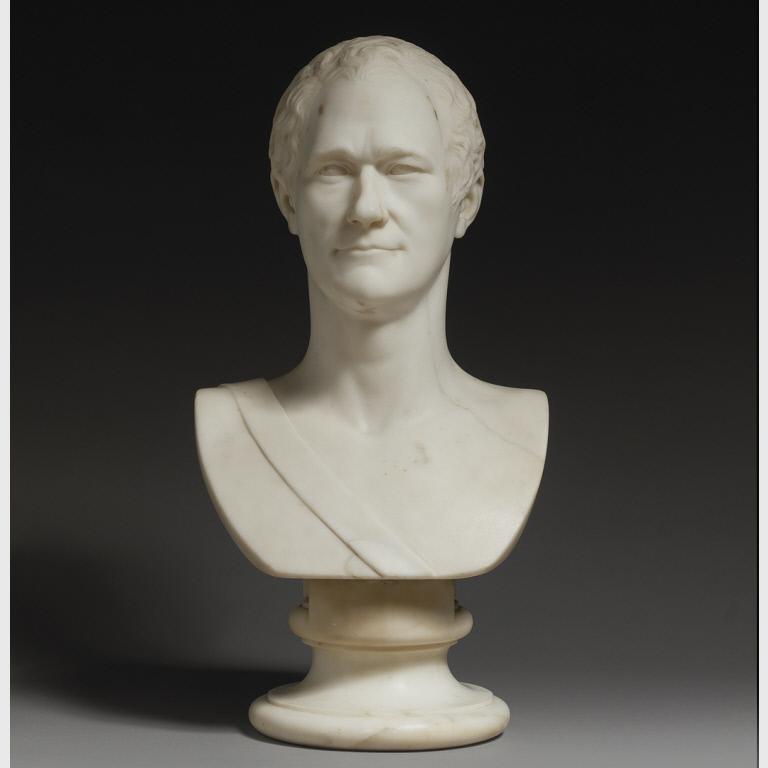

Giuseppe Ceracchi, Alexander Hamilton, 1794. Marble, 25 x 12 x 14 in. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

By Amy Torbert, 2015-16 Tyson Scholar

Amy Torbert was a 2015-2016 Tyson Scholar in American art at Crystal Bridges. She is a PhD candidate in art history at the University of Delaware. During her nine-month stay at Crystal Bridges, from September 2015 through May 2016, Amy worked on her dissertation about depictions of the American Revolution by eighteenth-century British printmakers. Following the completion of her time in Arkansas, she will become the 2016-2017 Barra Fellow in American Art at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

The Tyson Scholars of American Art Program is a residential program that supports full-time scholarship in the history of American art, visual and material culture from the colonial period to the present. The program was established in 2012 through a $5 million commitment from the Tyson family and Tyson Foods, Inc.

In 1896, The Atlantic Monthly published an article titled “Reminiscences of Mrs. Alexander Hamilton.” The anonymous author recalled spending the summer of 1852 with Hamilton’s widow, Eliza Schuyler Hamilton (1757–1854), when he or she was 13 years old and Mrs. Hamilton was 95. The author wrote:

“I remember nothing more distinctly than…a marble bust of Hamilton standing on its pedestal in a draped corner. That bust I can never forget, for the old lady always paused before it in her tour of the rooms, and leaning on her cane, gazed and gazed, as if she could never be satisfied.”

1. Giuseppe Ceracchi, Alexander Hamilton, 1794. Marble, 25 x 12 x 14 in. Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Fast-forward 165 years: the exact same bust that held Eliza’s attention now graces the galleries at Crystal Bridges (fig. 1). When strolling through the Museum on your next visit, pause for a moment when you enter the first gallery and step into Eliza’s shoes as you stand in front of the marble bust that helped her keep Hamilton’s memory alive. Though the sculpture was created to honor its sitter in life, his untimely death transformed it into a lasting memorial.

In January 1791, the Italian sculptor Giuseppe Ceracchi (1751–1801) arrived in America, motivated by his interest in revolutionary causes and by the hope of creating an equestrian sculpture of George Washington. While this commission never came to fruition, Ceracchi spent the next 18 months sculpting portraits out of clay of 27 “Great Men of America,” including Alexander Hamilton (1755–1804), John Adams, John Jay, Thomas Jefferson, James Madison, James Monroe, and George Washington.

The sculptor wrote to Hamilton from Amsterdam in July, 1792. He was on his way back to Italy, where he said he “will have the satisfaction of driving my chisel into marble to develop some American heroes. This is why, my dear sir, I am impatient to receive the clay [bust] I had the satisfaction of forming from your witty and significant physiognomy” [source]

Like any good salesperson, Ceracchi was hoping that flattering his client would lead to an even larger commission: he was trying to convince Congress to fund his scheme for “a monument to perpetuate American liberty and independence,” a project that would stand 60 feet high, take 10 years to complete, and cost the equivalent of approximately $2 million in 2016 US dollars. Though Congress rejected this extravagant proposal, Ceracchi persisted in sculpting busts of Hamilton, Washington, and Jefferson in marble during his two-year stay in Italy.

After running into trouble with the papal authorities in Italy for his liberal views, Ceracchi returned to the United States in 1794 carrying his three marble busts. At first, he offered the busts to their sitters as gifts—Hamilton and Jefferson accepted theirs, though Washington declined his, believing it inappropriate for the President to accept such a gift. Hamilton initially paid Ceracchi only $2.80 “for freight &c of my bust” on July 14, 1795. Within the year, however, Ceracchi demanded his recipients pay for his time and materials. Hamilton acquiesced and sent Ceracchi $620 (or approximately $11,000 today), though he noted with annoyance, “this sum through delicacy paid upon Cherachi’s draft for making my bust on his own importunity & as a favour to him.”

Giuseppe Ceracchi, Alexander Hamilton, 1794 (detail).

Though this exchange might have left a bitter taste in Hamilton’s mouth, the bust itself has shaped how future generations imagine him. Hamilton appears in the guise of a Roman statesman with a classical profile and strong nose. A slight smile plays about his lips, while his furrowed brow suggests his powerful mind at work. Depicted as heroically nude, save for a single strap across his right shoulder, this portrayal in a neoclassical style reinforced the democratic ideals of the new American republic, whose leaders consciously chose to associate their nation with the ancient democracies of Greece and the republican values of Rome.

The bust also struck Hamilton’s contemporaries as the most accurate depiction of its subject. In the wake of the massive public outpouring of affection after Hamilton’s death in 1804, numerous copies of Ceracchi’s sculpture were made in both marble and plaster. John Trumbull used the bust as the source for the portrait he was commissioned to paint for New York City Hall immediately after Hamilton’s death. And in 1929, when the U.S. Federal Reserve decided to place Hamilton’s portrait on the redesigned $10 bill, they selected Trumbull’s interpretation of Ceracchi’s bust as the iconic image of the first Secretary of the Treasury. Through its replication, as well as its persistent physical presence, Ceracchi’s bust has kept Hamilton’s memory present and tangible for subsequent generations.

![John Trumbull, Alexander Hamilton ], 1804–1805. Oil on canvas, 94 x 60 in. City Hall Portrait Collection, Collection of the City of New York.](https://images.crystalbridges.org/uploads/2016/05/Figure-4.jpg)