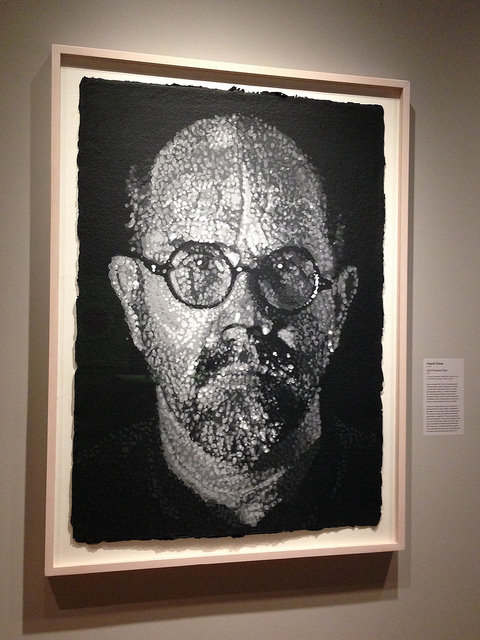

Chuck Close, b. 1940

“Self Portrait/Pulp,” 2001

Colored pressed handmade paper pulp consisting of eleven various grays

One of the most arresting works in the newly re-configured 1940s to Now Gallery is Chuck Close’s self-portrait. This large-scale black-and-white artwork looks, at a glance, like an Impressionistic rendering made up of blobs of white, gray, and black paint. But look closer: the work is actually made of paper pulp in varying shades, which has been squeezed through stencils in many layers to create the final image.

Close was born in 1940 and began his career creating works inspired by the Abstract Expressionists. He abandoned this style in the 1960s, however, and began create photorealist portraits in a wide variety of media, including the old-fashioned daguerreotype and mezzotint, and ranging to paint, paper pulp, thumbprints, tapestry, and watercolors applied through a printer.

One of the things that makes Close’s work fascinating to study is the method he uses to create them. Close suffers severe dyslexia and “face blindness,” or prosopagnosia which makes it very difficult to remember and recognize faces. He found contemplating an entire face at once to be “overwhelming,” and so he began breaking faces up into gridded segments, focusing on each square individually. The process was also a means of helping the artist imprint the faces of loved ones on his memory.

Chuck Close, b. 1940

“Self Portrait/Pulp,” 2001 (detail)

Colored pressed handmade paper pulp consisting of eleven various grays

Close begins with a photograph, which is blown up large and then overlaid with a grid pattern on an angle. Then, the artist works methodically through the squares, top to bottom, left to right, translating what he sees in each individual square to the canvas, sometimes using concentric circle or “hotdog” shapes, sometimes fingerprints, sometimes, as in this case, paper pulp. The viewer’s eye blends the colors or shades, a technique originating with the Impressionists in the nineteenth century.

Many viewers will see a similarity in Close’s work to pixelated digital imagery and the photomosaics that were popular in the late 1990s. However, Close began his process long before such technology existed. “I got there first,” he said, “so the computer’s like me, not the other way around.”

In 1988, Close suffered a spinal stroke: a collapse of one of the arteries supplying blood to his spinal cord. The stroke left him paralyzed from the neck down, and the artist spent eight months in the hospital. Over time, he gradually regained the use of his arms, though not of his hands. Today he paints with a paintbrush strapped to his wrist in front of a canvas on a mechanical device that raises, lowers, or turns the canvas as the artist wishes.

The paper pulp portrait is a time-consuming process, accomplished by studio assistants. A stencil is laid down and a single color of pulp is pressed through the holes and allowed to dry. Then another stencil is applied in a different color. Then another, and another, building up layers of paper to create the final image (see a time-lapse video of the process below).

If you have not had a chance to view this remarkable work, I encourage you to do so soon. Because this self-portrait is created of paper, it is light-sensitive, and therefore can remain on view for only a limited time. It will go back in the vault in mid-June.