Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bachman-Wilson House at Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art, Bentonville, Arkansas

Today is the birthday of Frank Lloyd Wright, great American architect and designer of the Bachman-Wilson House here on Crystal Bridges’ grounds. What do you know about Frank Lloyd Wright? Wright was a quirky, sometimes difficult personality, with a long career and complex life fraught with scandal and tragedy. Here are a few things you might now know about this American architectural icon:

Usonian Pet Designs

Wright once designed a miniature version of one of the residences he designed to serve as a doghouse for the family pet.

Also: Abe Wilson, original owner of the Bachman-Wilson House, designed and built a miniature version of their home to serve as a bird house for a crow his daughter, Chana, had befriended. She kept the birdhouse on the balcony of her bedroom, and the crow had freedom to come and go as it pleased.

A Toy Legacy

Wright’s original middle name was Lincoln, but he changed it to Lloyd to underscore his attachment to his mother’s family, the Lloyd-Joneses from Wales.

Lincoln Logs were invented by Wright’s son, John Lloyd Wright, and were based on the design of interlocking log beams for the base of the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, designed by Wright in 1916-1917.

Frank Lloyd Wright

A Mentor and an Enemy

Wright never graduated from high school. He attended one semester of college in Engineering at the University of Wisconsin around 1887, after which his interests switched to architecture. He went to work for John Selby: a rather mediocre architect in Chicago to gain experience, but primarily because Selby had connections to the famous architect Louis Sullivan, whom Wright idolized. He managed to get his designs in front of Sullivan, who admired Wright’s drawing skill and brought him on as a draftsman as he created new architectural designs for buildings to replace those that had been destroyed in the Chicago fire. Wright worked for Sullivan for 9 years.

While he was working for Sullivan, Wright was also secretly designing houses for clients on the side, without his boss’s knowledge or permission (these houses are now known as “bootleg” houses). Sullivan, who had mentored Wright and even loaned him money to build a house for himself, confronted Wright on this and fired him. Wright never repaid the money Sullivan had loaned him, and to add insult to injury, he created a competing architectural firm and located its offices on the top floor of the Schiller building, which Sullivan had designed. Although the two did not speak for 12 years after the falling out, Wright claimed to maintain the highest respect for Sullivan, and always referred to him as “mein lieber meister.”

Interior of the Guggenheim in New York City

The Guggenheim: Not An Instant Classic

When he was offered the opportunity to design the Guggenheim Museum in New York City, he refused to do it unless the building was bordered by nature on at least one side, a condition that required that an alternate site be selected for the building, bordering on Central Park. Wright’s unusual design for the museum features a spiral construction that carries visitors from the ground floor to the rotunda along a gentle sloping ramp around the walls. Wright designed the walls to lean slightly outward at the top, so that the artwork displayed on them be hung at a slight angle, in the same way it would be displayed on an easel. Before the museum opened, 21 artists wrote letters protesting this manner of exhibition. Some critics felt that the architecture of the museum overwhelmed the art. John Canaday, in the New York Times, referred to it as “a war between architecture and painting in which both come out badly maimed.”

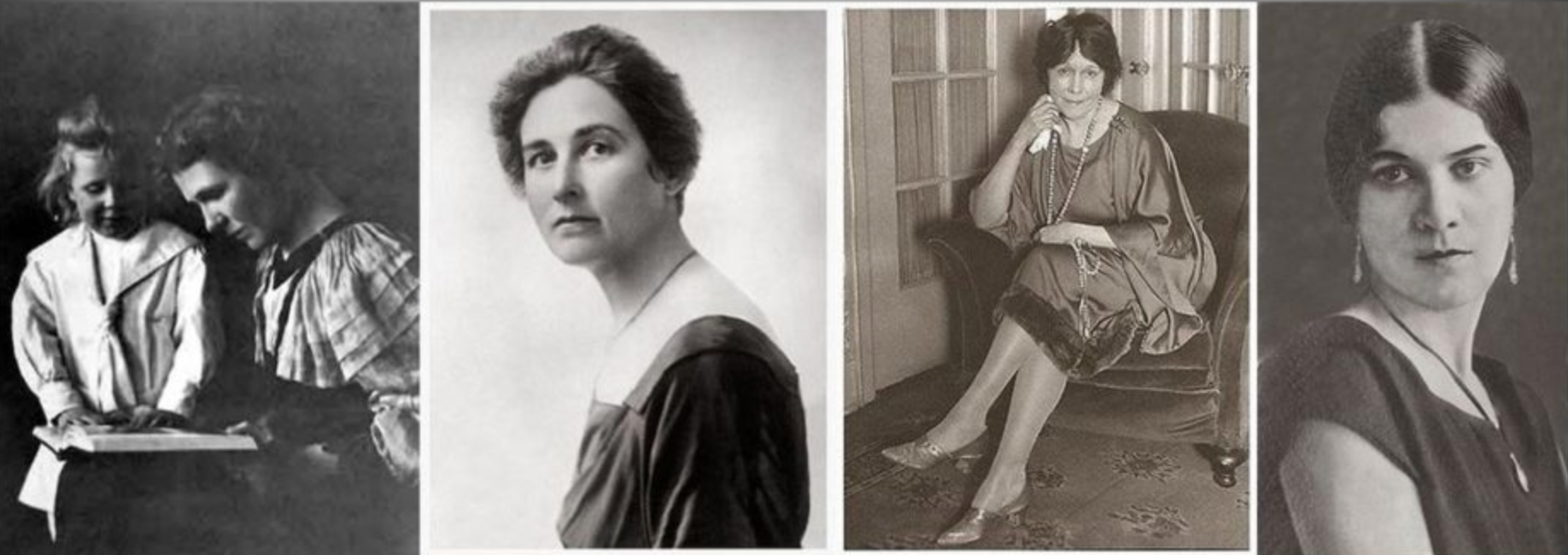

L–R: Kitty, Mamah, Miriam, Olgivanna

Something of a Playboy

Wright’s love life was famously scandalous. He married his first wife, Catherine Lee Tobin, in 1889. She was just 18. Catherine gave birth to six children with Wright, but in 1909, he left her for Mamah Cheney, the wife of one of Wright’s clients, who came to live with him at Taliesin, Wright’s famous Wisconsin home. It was a scandal that titillated society circles, but was later to be overshadowed in 1914 by Mamah’s murder, along with that of two of her children and four others, by a deranged cook at Taliesin while Wright was away in Chicago. The cook locked the dining room with the family inside it, set the house afire, and picked off anyone trying to escape with an axe. Six months after the murder, Wright’s new lover moved in to Taliesin: Miriam Noel, a wealthy divorcee whose money helped to restore the damaged house. In 1922, Wright finally obtained a divorce from Catherine and married Miriam, but only briefly. Miriam left him just five months later, and commenced divorce proceedings that dragged on for years. In 1924 Wright was seated next to the 26-year-old Olgivanna Lazovich Hinzenberg, a student of “sacred dance,” at the ballet in Chicago. Wright was 57. They hit it off right away, and a year later she joined him in Taliesin II, in Arizona, and bore him a daughter in 1925. They were married in 1928, and remained so until the end of Wright’s life in 1959.