In September, Crystal Bridges will exhibit an oil painting by John James Audubon, created in 1826 while the artist was in Edinburgh, Scotland. The painting depicts a family of wild turkeys: male, female, and seven chicks. It was based upon the individual watercolor paintings of the male and female turkeys that Audubon had already made for his collection.

The name John James Audubon is known and revered the world over. His great life’s work, the ambitious and breathtaking Double Elephant Folio, Birds of America, captured images of nearly 500 species of American birds, several of which are now extinct, including the Carolina Parakeet, Passenger Pigeon, and Great Auk. It is estimated that only around 200 of the original edition were printed. Of these, a mere 120 are now known to exist.

While everyone is familiar with Audubon’s work, the artist’s personal history is less familiar, and surprisingly colorful. He was born “Jean Rabin” in 1785 in Santo Domingo, Haiti (now the Dominican Republic) to Jeanne Rabin, a chambermaid in a plantation which neighbored that of the boy’s father, Jean Audubon, a French captain and mercantile agent. Jeanne died when the boy was an infant.

During the slave revolts in 1789, Audubon Sr. sent Jean (and his half-sister by yet another mistress) to his home in Nantes, France, where they were raised and loved by Audubon’s wife, Anne Moynet. Both siblings were formally adopted by the couple in 1794.

Due to civil unrest in the region, the young man’s education in Nantes was spotty, but he did gain the basics of dancing, fencing, and violin. He also spent a good deal of time in the fields and forests: exploring, making collections of birds’ nests and eggs, and drawing. He was already an avid but untrained artist, though he later claimed, falsely, to have been a student of the famous French portraitist Jacques Louis David.

In 1803, to avoid his son being drafted into Napoleon’s army, Jean’s father once again sent him overseas. This time Jean went to America, where he was to take charge of a farm his father owned in Mill Grove, Pennsylvania. In America, Jean was able to present himself as his father’s legitimate son, and thus he went by a new name: John James Audubon.

In Mill Grove, Audubon continued to knock about much as he had in Nantes: shooting and drawing birds, ice skating, dancing, riding, and generally leaving the running of the farm to the Quaker tenants. He was young, handsome, and comfortably well off, though this was the only period of his life during which finances were not a problem.

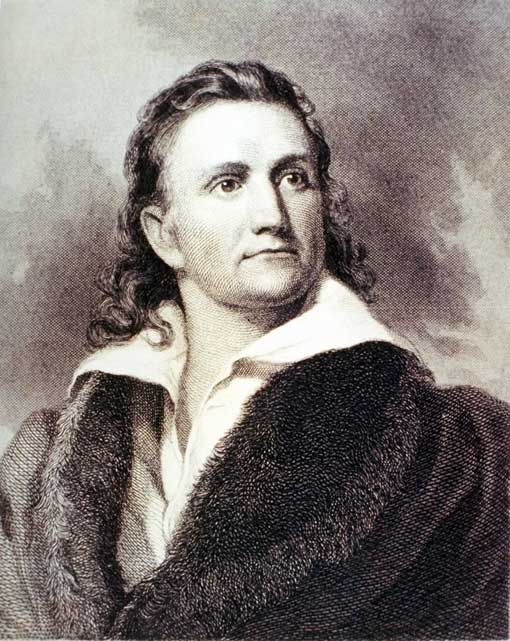

He is described by contemporaries as extremely good-looking, and was referred to by one friend as “one of the handsomest men I ever saw. In person he was tall and slender, his blue eyes were an eagle’s in brightness… his hair a beautiful chestnut brown, very glossy and curly.”

Though he was much in demand among the ladies of the district, Audubon gave his heart to Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of an English neighbor, whom he married in 1907. Despite their auspicious beginnings, their life together would be a difficult one, filled with hardships, failure, penury, loss, and separation.

The same year he married, Audubon sold his share of the farm and relocated to Louisville, Kentucky, where he and a business partner set up a store. Unfortunately, Audubon had no head for business, and left the running of things almost exclusively to his partner. He wrote: “I shot, I drew, I looked on nature only; my days were happy beyond human conception, and beyond this I really cared not… I seldom passed a day without drawing a bird….”

One day a naturalist and artist named Alexander Wilson came by Audubon’s store, seeking subscriptions for his publication American Ornithology, a collection of prints to be made from Wilson’s paintings of American birds. Audubon later related the story in his Ornithological Biography: “I felt surprised and gratified at the sight of the volumes, turned over a few of the plates, and had already taken a pen to write my name in his favor when my partner rather abruptly said to me in French, ‘My dear Audubon, what induces you to subscribe to this work? Your drawings are certainly far better, and again you must know as much of the habits of American birds as this gentleman.’ … Vanity and the encomiums of my friend prevented me from subscribing.”

Seeing Wilson’s work sparked an ambition in Audubon to create his own collection of paintings of American birds: a dream that would take him nearly 30 years to realize.

Stay tuned for Part 2, coming soon.