Happy PRIDE Month! Throughout history, the art world often offered “safe spaces” of acceptance for people’s differences, and signified that there was a place of belonging for those who felt outcast and marginalized, a place that was welcome to all, just like Crystal Bridges is today.

Here, we’d like to examine the storied histories of a few artists and artworks in the Crystal Bridges collection that identify as queer*.

Sappho

A tour guide gives a lecture on Sappho during 2019’s PRIDE Night event.

In the Early American Art Gallery at Crystal Bridges, the carved marble sculpture of Sappho sits strong and proud. Visitors stop to admire her beauty every day, and the sixth-century-BC poet was a favorite among artists in the late nineteenth century. Sappho is also an important figure in lesbian history, from the island of Lesbos (which is where the term “lesbian” originates). Although most of Sappho’s writing is now lost, she did write about same-sex attraction among women that was later picked up by lesbian women who identified with her words. This example signifies that queer history dates back at least to ancient Greece, and has been reflected in the art world since that time.

Paul Cadmus and George Tooker

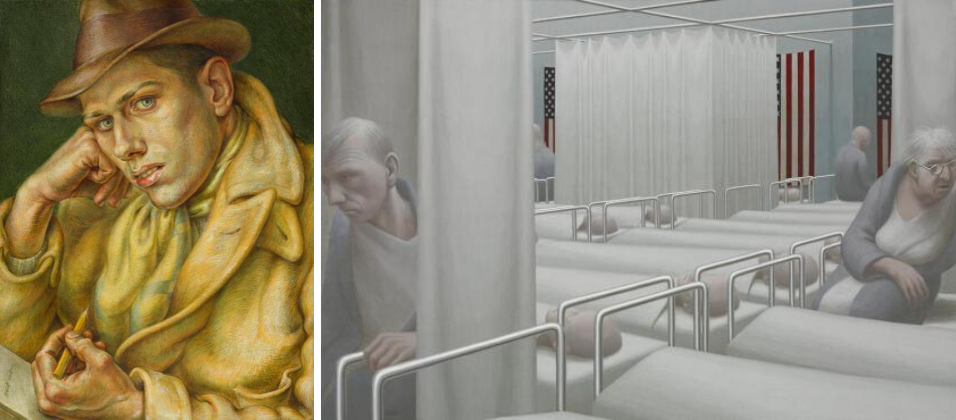

Left: Paul Cadmus, Self-Portrait, 1935, 16 x 12 in. (40.6 x 30.5 cm), tempera on board, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art. Right: George Tooker, Ward, 1971, 20 x 30 in. (50.8 x 76.2 cm), tempera on panel, Promised Gift to Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

In his Self-Portrait (1935), Paul Cadmus stares out defiantly to his viewers, clutching a pencil firmly in his hand. He almost looks like a Dick Tracy detective, wearing an upturned coat and fedora, penning out the clues of his mysterious case. But in many ways, that’s what Cadmus was to observers: a mystery. In Fences (1946), Cadmus painted his long-time lover, Jared French, as an elongated nude figure standing against a pole on a beach on Fire Island, New York—a long stretch of beach that was considered a safe haven for young gay men throughout the twentieth century and up to today.

During this same time period, George Tooker, a peer and colleague of Cadmus’s, explored themes of love, death, sex, grief, and aging through egg tempera painting. Much like Cadmus, Tooker’s lived experiences on the social periphery of the twentieth century influenced the themes and style of his art, such as portraying anxiety and alienation in modern society, as seen in paintings like Ward (1971). In this way, he was a pioneer in using art to question contemporary society.

Jeffrey Gibson

Jeffrey Gibson, What We Want, What We Need, 2014, 71 × 14 × 14 in. (180.3 × 35.6 × 35.6 cm), found punching bag, glass beads, artificial sinew, copper jingles, nylon fringe, and steel chain, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Contemporary Indigenous artist Jeffrey Gibson grew up mainly abroad in West Germany and South Korea, as his father worked for the US Defense Department delivering supplies to military bases. This experience left him wondering about his identity. Having never actually lived on a US reservation as a Choctaw-Cherokee or experiencing the AIDS crisis of the 1980s as a gay man, Gibson questioned his role in these communities—where did he stand in his identity? Gibson’s artwork and exhibitions have focused on themes that have helped find these answers. For example, in What We Want, What We Need, Gibson examines opposing forces in society—power and domesticity, femininity and masculinity, etc.—and how they can blend harmoniously, like beadwork on a punching bag.

Cobi Moules

Cobi Moules, Untitled (Yellowstone, Swan Lake), 2014, 36 × 46 × 2 in. (91.4 × 116.8 × 5.1 cm), oil on canvas, courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

By placing himself within a landscape inspired by Hudson River School paintings, Cobi Moules seeks to ennoble what he calls the “experiences related to [his] trans and queer identity.” In the Western tradition, large landscapes communicated the overwhelming power of nature and God. Moules embraces that tradition while intentionally disrupting it with the introduction of many selves. Here, he responds to his upbringing, challenging the idea that his gender and sexual orientation are unnatural—against God. Moules multiplies his own body, consuming the entirety of the landscape, attempting to redefine his relationship to God and nature.

Vanessa German

Left: Vanessa German stands in front of the ART House in Homewood, Pittsburgh. Right: Vanessa German, Artist Considers the 21st Century Implications of Psychosis as Public Health Crisis or, Critical/Comedic Analysis into the Pathophysiology of Psychosis, 2014, 40 × 55 × 26 in. (101.6 × 139.7 × 66 cm), mixed media assemblage, courtesy Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Vanessa German identifies as female, African American, and queer, and has experienced the hardships that come along with these labels. She uses sculpture as a way to finally do anything she wants, with no limitations inhibiting her. Vanessa German’s “power figures” feature a plethora of found objects purposefully attached to black dolls. While each sculpture exists as a single work, they are composed of a wide array of materials that each impart their own story—all combining to create a sculpture imbued with beauty and magic. Mixing complex historical references with playful elements, German creates ean opportunity for viewers to explore and discover what she refers to as “an adventure in sight.” Learn more about Vanessa German here.

Nick Cave

Left: Artist Nick Cave gives a talk during 2019’s Meet the Momentary event. Right: Nick Cave, Soundsuit, 2010, 97 x 48 x 42 in. (246.4 x 121.9 x 106.7 cm), appliquéd found knitted and crocheted fabric, metal armature, and painted metal and wood toys, Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art.

Since the mid-twentieth century, the number of dance styles in the United States has accelerated dramatically, inspiring new collaborations between the art and dance worlds. Nick Cave is both dancer and artist, and this sculpture is a result of the marriage of his two roles. This Soundsuit is more than a costume designed for performance; it is an empty vessel charged with potential energy. When worn, the movement of the wearer causes the suit to produce its own sounds as the elements are activated. This, in turn, directs the dancer on how to move. Dancer and artwork are two parts of a whole–each informs the other in order to harness the spirit of dance.

Gabriel Dawe

A tour guide gives a lecture on Plexus No. 27 by Gabriel Dawe during 2019’s PRIDE Night event.

Gabriel Dawe’s work stems in part from his background. He grew up in Mexico City watching his grandmother create hand embroidery, a skill she passed on to her granddaughters but not her grandson. Here, he transforms a traditionally feminine medium into a comment on the social norms that often rule our everyday lives. In Plexus No. 27, Dawe strings miles of colored thread between hooks on the walls, creating mesmerizing color, form, and shadows. As you move around it, the overall shape of the work changes depending on your position in the space. Dawe’s approach reminds us that each viewpoint derives from a unique set of circumstances, and our shared challenge is to be open to multiple points of view.

***

With an understanding of the importance of queer artists’ contributions to the art-world canon, and with a goal of continuing to educate visitors, we can represent the breadth and depth of the American experience in our collections and provide a safe space where all visitors can feel reflected on the museum walls.

*To clarify, when we say the word “queer,” we are referring to a self-identification of a person that is not heterosexual or cisgender (having a gender identity that matches the sex assigned at birth). It is important to note that for many, the term “queer” can be problematic, as it is a reflection of a negative history, but for others, “queer” is how they self-identify, which is why we use the word.