We’re entering the last days in which guests may view the temporary exhibition American Encounters: Anglo-American Portraiture in an Era of Revolution, on view here at Crystal Bridges through September 15. Don’t miss this lovely assemblage of portraits from the collections of Crystal Bridges and our partner institutions: the Musée du Louvre in Paris, the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, GA; and the Terra Foundation for American Art, Chicago. In this, the first in a two-part blog series, Curator Manuela Well-Off-Man discusses the connections between the five portraits included in the exhibition. –LD

When Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art opened in 2011, the Museum had already established successful partnerships with other museums and made works from its permanent collection available to these institutions. A wonderful example of Crystal Bridges’ collaborations with other museums is the traveling exhibition series American Encounters. This year’s exhibition, organized by Crystal Bridges, is titled American Encounters: Anglo-American Portraiture in an Era of Revolution. It is the third of a four-part series of exhibitions. One goal of this exhibition series is to share significant works from each institution’s early American art collection with their audiences. These annual focus shows are also a great opportunity to create new scholarship and to provide new art and education experiences. This year’s exhibition highlights five portraits that explore artistic influences and political encounters among a group of interconnected artists and patrons in America and Europe during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In addition, four works from Crystal Bridges’ permanent collection support the exhibition’s theme while American Encounters is on view here at the Museum.

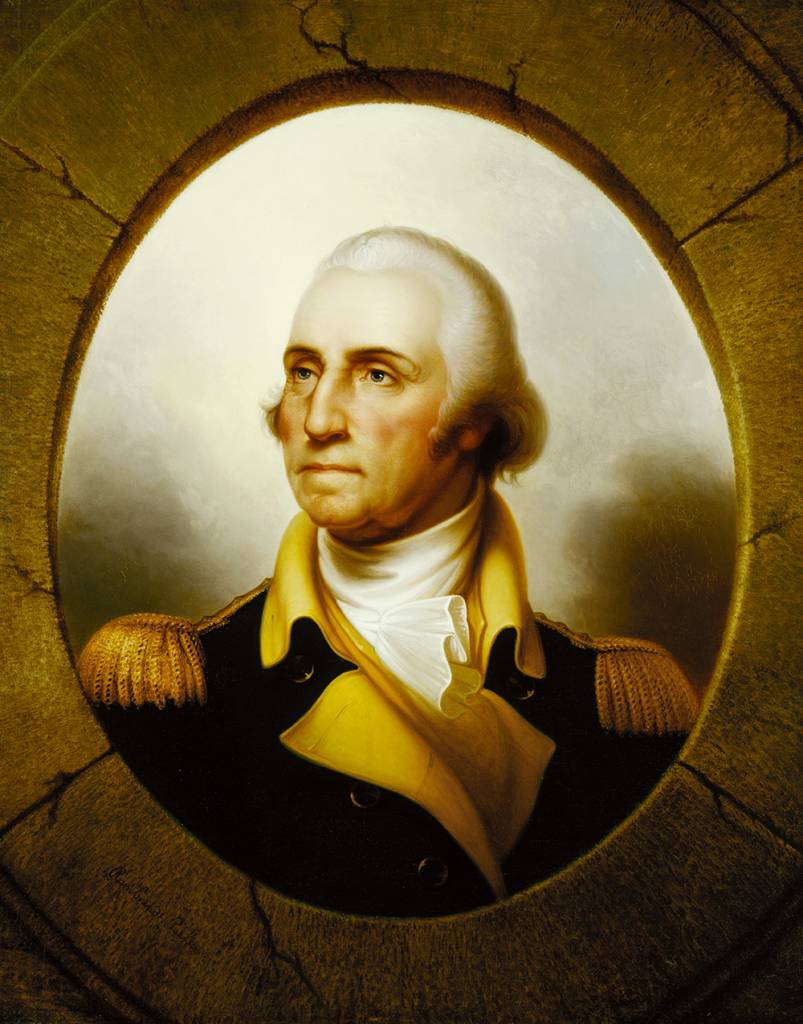

Charles Willson Peale

Portrait of George Washington

c. 1779

Oil on canvas

Versailles, musée National du château

Guests will immediately notice the three portraits of George Washington in the exhibition. They represent different stages of his political career, as well as his changing roles during this era of revolution and conflict. The paintings also indicate the popularity of the first president’s likeness in America and Europe during that time. Charles Willson Peale’s George Washington after the Battle of Princeton, January 3, 1777, presents Washington as the commander in chief of the Continental Army and commemorates his victory over Britain in this famous battle. Charles Willson Peale actually participated in the Revolutionary War: he joined Washington in the first crossing of the Delaware and fought with him in the battle of Trenton in 1776.

Gilbert Stuart

“Portrait of George Washington” (The Constable Hamilton Portrait)

Oil on canvas

Crystal Bridges

Gilbert Stuart’s George Washington [The Constable-Hamilton Portrait] (1797) depicts the nation’s first president at age 63, at the end of his political career. The portrait addresses Washington’s professional roles and accomplishments. The sword on his lap refers to his past success as commander-in-chief during the Revolutionary War, and the signed paper hints at his position as a lawmaker and diplomat. Along with the merchant ships in the background the document Washington holds very likely refers to the Jay Treaty (1795), which regulated trade issues between Great Britain and the United States.

The third portrait of Washington was painted in 1824 by Charles Willson Peale’s son, Rembrandt Peale, and is one of the best-known Washington portraits today. Decorated with a golden trompe l’oeil frame, this portrait celebrates Washington as heroic military commander and successful first president of the young nation. George Washington (Patriae Pater) is a posthumous glorification of the Father of the Country, and one of 79 copies of the original version which was acquired by Congress in 1832.

Interestingly, all three artists who portrayed Washington belonged to a group of American painters who studied under American-born Benjamin West at the Royal Academy in London. Their portrait styles showed certain influences of British and European state portraiture, which they brought back with them to America. However, they each developed their individual styles and carefully “translated” these influences from oversees for their American patronage and audience.

Gilbert Stuart

“Hugh Percy, Second Duke of Northumberland,” c. 1788

Oil on canvas

Atlanta High Museum, 1993.14

Gilbert Stuart’s second work in the exhibition, his Portrait of Hugh Percy, Second Duke of Northumberland was painted in London ca. 1788, the year the artist fled to Ireland to escape his creditors. Unlike Peale, Stuart did not participate in the War of Independence and fled America at the beginning of the Revolution. Stuart was more talented as an artist than in financial matters, and the commission of Hugh Percy’s portrait probably saved him from debtor’s prison. He rendered the duke with a gentle smile in a horse grenadier’s uniform, decorated with the Star of the Order of the Garter, the highest and oldest order of chivalry in England, which he received in 1788, about the time when his likeness was painted. Although Hugh Percy had loyally served in the British Army between 1775 and 1777 he was critical the British aggression toward the American colonists.

Scottish artist Sir Henry Raeburn painted the impressive full-length portrait of Robert Hay of Spott and Lawfield [image] shortly before Hay retired from the army in 1795. The Scottish nobleman was First Lieutenant of the 23rd Infantry Regiment, also known as the Royal Fusiliers, one of the oldest regiments of the British Army. They participated in almost all battles of the American Revolutionary War, and it is likely that Hay also fought in this war at the beginning of his military career. Raeburn usually painted from life, and unlike most of his artist peers he did not make preliminary sketches. Instead he worked intuitively, which resulted in less refined, softer modeling, anticipating the techniques of modern art movements such as Impressionism. His style contributed to the popularity of military-style portraits for the male British gentry. However, Raeburn’s military likenesses seem more lively and sensuous compared to military portraits by contemporary artist peers.

In the Next Post: We’ll talk about the works from Crystal Bridges’ permanent collection that accompany this exhibition.